WHAT IF? (Part 3c: But wait...there's more!)

October 26, 2019

October 26, 2019  The hazelnut orchard next to our trailer this summer. See end of post for why the ground is so bare.

The hazelnut orchard next to our trailer this summer. See end of post for why the ground is so bare.

My unplanned foray into the world of hazelnuts has one more twist. When I researched hazelnut farming practices I discovered some surprises.

The Willamette Valley is Hazelnut Central, growing about 99% of U.S. hazelnuts, otherwise known as filberts. A major threat to this crop is the filbertworm, the larva of the moth, Cydia latiferreana, also native to the area. The moth lays its eggs near the nuts and the larva burrow through the shell to munch on the kernal, leaving nothing to collect come harvest. The common practice for hazelnut farmers is to spray a pesticide to kill the eggs or the newly-hatched larvae before they have a chance to enter the nut.

Because of the skill of the filbertworm, organic hazelnuts are rare, with a mere 1% of hazelnuts being grown this way. And there is an interesting catch to organic hazelnut production. Even if the worm can be eliminated on the orchard itself, the worm lives on native white oak trees (Quercus garryana) and so oaks neighboring organic orchards are a source of re-infestation of the hazelnut trees.

Because of this, organic hazelnut growers may be encouraged to cut down native oaks on their property.

WHAT...?!!!?

Suddenly my plan to buy organic hazelnuts doesn't seem so great.

Oaks in the Willamette Valley and surrounding mountains are part of two ecosystem types: oak woodlands and oak savannas. The oak savannah is actually a grassland, with scattered single oaks that grow broad canopies due to the lack of neighboring trees. The Willamette Valley was once covered with oak savannas, but with changing human priorities, only a tiny fraction of this ecosystem remains, perhaps less than 1%. Oak woodlands are also increasingly rare, with around 5 - 7% remaining. Much of the remaining oak habitat is privately owned and on agricultural land, so this clash between sustainable farming methods and oak conservation is important.

If I was going to make a list of trees I would most like to be friends with, oaks are top candidates, along with cottonwoods and aspens. Their massive limbs and calm presences make them look like elder beings striding along over the grassy hills or settled into the draws. There is a small cluster of oaks along a seasonal stream about a mile from Tom’s parents’ house and I walk there frequently on hot days to feel the sudden coolness under the trees, and listen to the chatter of birdsong in the branches. After the hot asphalt road or the bare Christmas tree fields, this oasis of life is a welcome relief.

So it's a shock to me that my organic hazelnuts could be coming at the expense of my beloved oak trees.

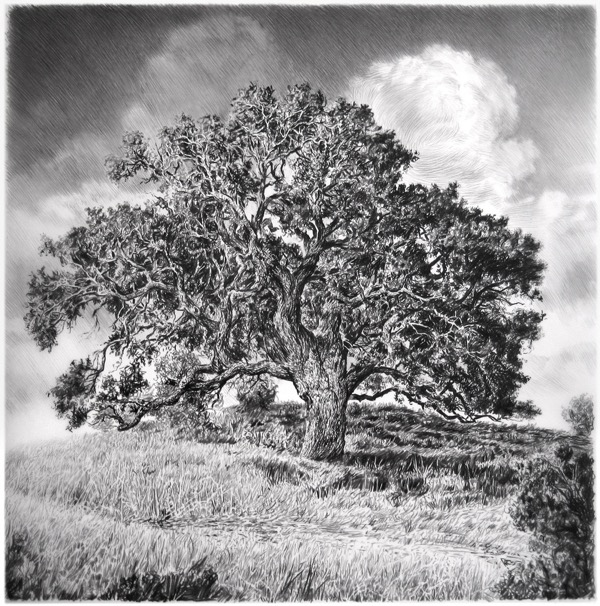

© Rick Shaefer Used by permission of artist.

© Rick Shaefer Used by permission of artist.

And it reminds me that things are never simple. John Muir’s oft-quoted thought, “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe,” applies just as much to organic farming as anything else. More and more we find that not only do environmental goals collide with large-scale food production, but that different environmental goals also collide with each other. As I said in the last post, affliction is an inevitable part of life.

There are no easy answers.

And ironically, fully recognizing that seems like a step toward grace.

I was planning to end this article with a discussion of research collaboration between the University of Oregon and an organic farm to try grazing pigs under their trees as a way to reduce the number of filbertworm larva overwintering in fallen nuts.

I was going to use this as an opportunity to talk about how complex systems need complex responses—and that no matter how much we try to simplify it, the world we live in is complex.

I was going to talk about different disciplines working together—how growing food requires a knowledge of history, ecology, agriculture, demographics, philosophy, etc. For example, understanding that oak savannas in the Willamette Valley were probably maintained by Kalapuya and other local Native American groups using controlled burning. Or recognizing that there are over 140 different species of wildlife that use oaks for resting, feeding, or nesting. Or knowing that timing of agricultural activities and crop selection makes a difference. Or identifying the cultural values underlying our food production systems and recognizing the impact these values have on our surroundings.

But as I tried to do this, I realized that I was doing exactly what I said we shouldn't do. I was proposing an "answer". I was making complexity into something that we could imagine being in control of. I was making it too simple.

I would like to resist doing that at least for the time it takes to finish reading this post. I would like to hold the questions as questions. To leave it open. To just pause.

And perhaps in that pause, this quote from Rainer Maria Rilke that my sister reminded me of recently would be relevant:

...be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.

—Rainer Maria Rilke

Young oak tree contemplating the future.

Young oak tree contemplating the future.

-------------------

ENDNOTES

A note about the drawing by Rick Shaefer: this is actually a type of oak called a "live oak" not a white oak, but Rick so captured the feeling of reverence that I have toward oaks, as well as the Tree's place in the savanna habitat, that I decided to use it anyway. Rick's work is impressive, both for its skill and the global scale of his view—I highly recommend a look at his website, especially his recent piece, The New Colossus, about Wall Building.

If you would like to read more about the research I referenced above, click here for a short synopsis of my own, and here for links to the project itself.

And I promised to tell you why the ground is so bare around hazelnut trees. The short answer is for harvest, as hazelnuts are collected by sweeping them off the ground after they fall. But the more I look, the more convoluted the reasoning gets. Bare ground means less habitat for filberworm larva and other insects. Bare ground means fewer ground squirrels and gophers who gnaw on tree roots. Moles would eat the insects, but they leave mounds that interfere with the harvesting equipment. Ground cover would help soil fertility but it also attracts more bees, so less ground cover means fewer bees are killed by insecticides. And on and on... The complexity of the reasons for simplifying an environment so dramatically point to the complexity of the actual system, regardless of how simple we try to make it.

Ecology

Ecology